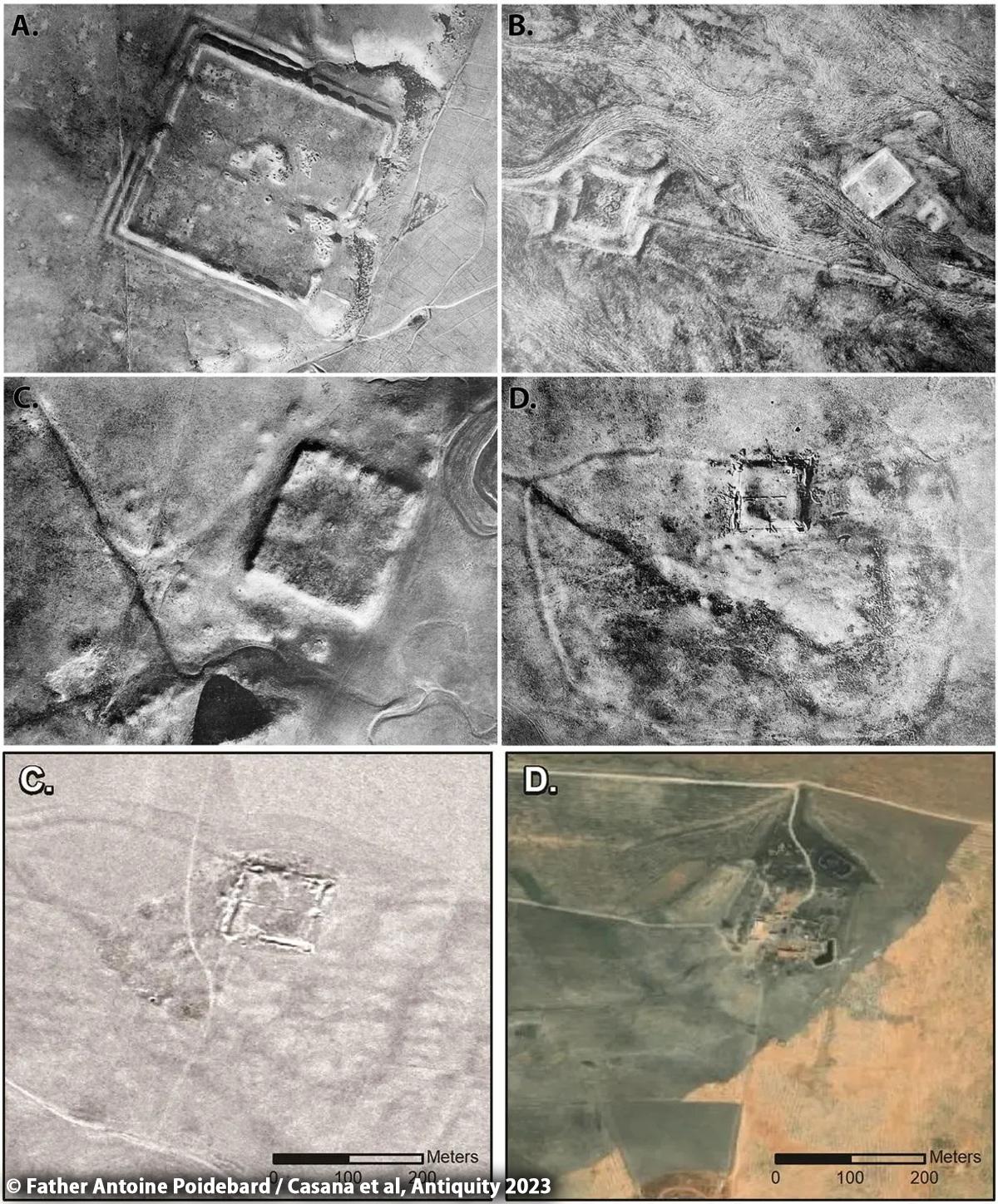

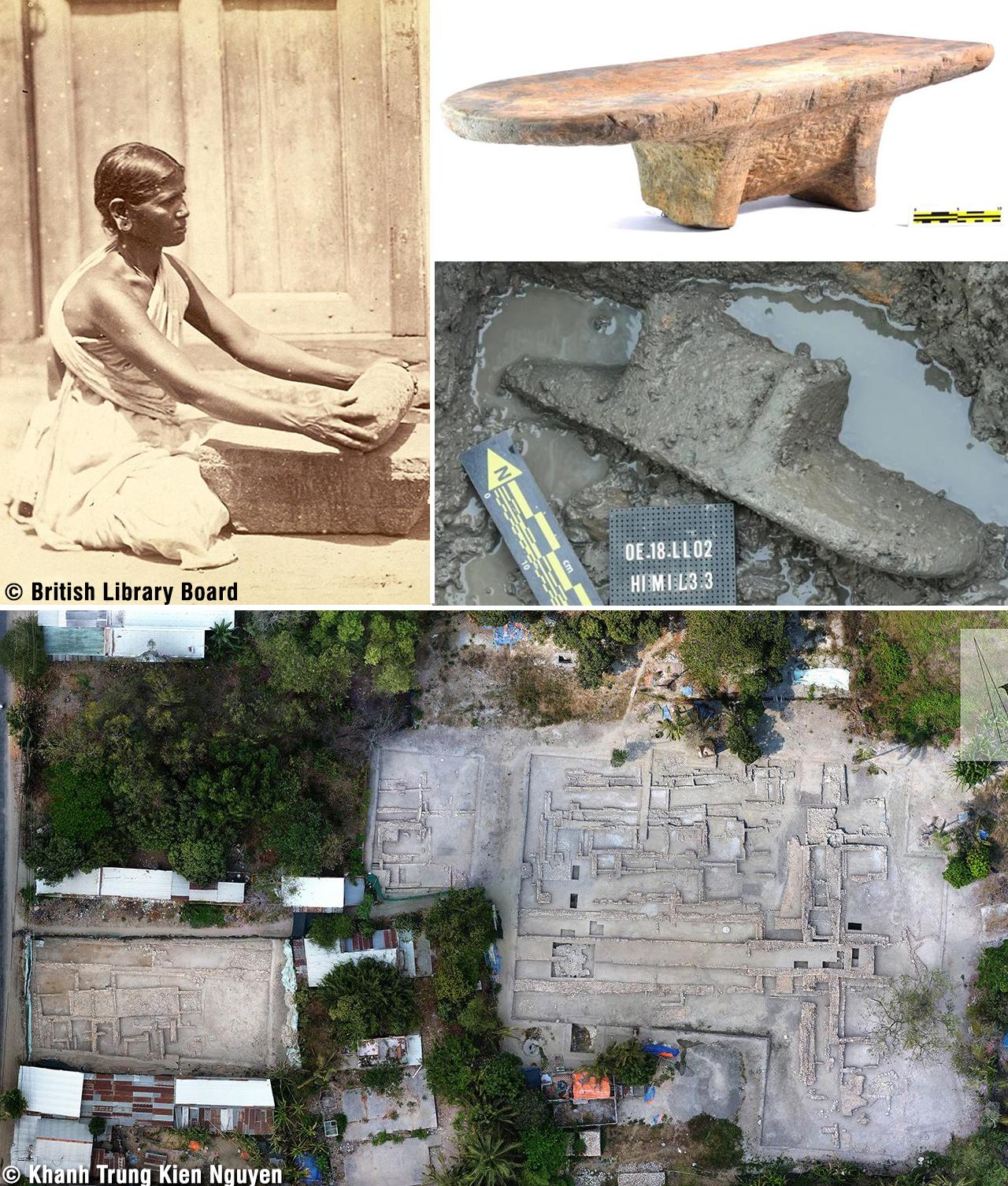

Pompeii, the Roman city preserved in time by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, continues to reveal captivating insights into ancient life.

Electoral inscriptions have been discovered in an ancient house at Pompeii. Courtesy of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii

Recent excavations along the Via di Nola in central Pompeii have unveiled electoral inscriptions inside a house, offering a glimpse into the politics of the time, a connection between politicians and bread, and the last rituals performed before the city’s devastation.

Typically, electoral inscriptions were displayed on the outer facades of buildings, enabling citizens to read about candidates vying for city magistracies. However, the surprise lies in their discovery inside a house, a practice explained by archaeologists who note that hosting campaign events and dinners within candidates’ homes was customary in ancient Rome.

These signs endorse Aulus Rustius Verus, a candidate for the position of aedile, a councilor responsible for public works in ancient Rome. Aulus Rustius Verus held the highest public office in Pompeii in the first century CE, suggesting that these inscriptions are older, likely from his successful election campaign.

Courtesy of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii

The house where these inscriptions were found may have belonged to a fervent Aulus Rustius supporter, potentially a freedman or a close friend. Of particular interest is the discovery of a bakery with a large oven within the house. Near the bakery, archaeologists found the tragic remains of three victims, two women, and a child, who perished during the eruption.

This bakery’s presence underscores the existence of political patronage in ancient times, similar to today’s vote-buying practices.

Maria Chiara Scappaticcio, a professor of Latin at the Federico II University in Naples and co-author of the study, pointed out that councilors and bakers “collaborated to the limits of legality” in ancient Rome. Aulus Rustius Verus seemed to understand the importance of providing voters with bread. This connection is reinforced by the discovery of the candidate’s initials, ARV, on a volcanic millstone within the house, suggesting direct financing of the bakery by Aulus Rustius Verus for both economic and political purposes.

In addition to the electoral inscriptions, archaeologists found evidence of a final votive offering on the altar of the Lararium, adorned with stucco snakes. This ritual, likely conducted shortly before the eruption, involved burning figs and dates in front of the altar, concluding with the placement of a whole egg on the masonry altar, covered with a tile. Previous offerings included vine fruits, fish, and mammal meat.

The findings in Pompeii provide an intriguing window into the realm of politics in ancient Rome. The presence of Aulus Rustius Verus’s endorsements, the connection between political clientelism and a bakery, and the rituals at the Lararium all contribute to a richer understanding of life in Pompeii before its tragic end.